A guest post from Olaf Schroth on the Vancouver Game Design Expo:

On April 10 and 11 2010 the fourth annual Game Design Expo 2010 took place in Vancouver. The event was hosted by the Vancouver Film School (VFS) which has a strong course program in gaming and features speakers including Armando Troisi, Lead Cinematic Designer on BioWare’s runaway hit Mass Effect 2, who discussed the game’s approach to interactive narrative, and United Front Games’ William Ho, who explored user-generated content through the lens of the highly-anticipated PS3 title ModNation Racer.

Other speakers included creative movers from the legendary California-based developer Obsidian Entertainment (Alpha Protocol), Blue Castle Games (Dead Rising 2), Propaganda Games (Tron: Evolution), and Big Sandwich Games (Sky Pirates of Neo Terra). The day ended with an industry panel hosted by Electric Playground’s Victor Lucas called “The Future of Gaming.” For this blog, I would like to report about two of the presentations, first about Armando Troisi and in a second post, about a fascinating approach to designing architectural spaces for Dead Rising 2.

Troisi: Bioware Roleplaying Games (RPG) – It`s all about choice

According to Troisi, the four Bioware Design Pillars are Story, Exploration, Progression and Game Play and through the course of every game, the player will cycle through these four elements multiple times. Thus, story always comes first for Bioware and Troisi focused on the Bioware way of storytelling.

According to Troisi, the four Bioware Design Pillars are Story, Exploration, Progression and Game Play and through the course of every game, the player will cycle through these four elements multiple times. Thus, story always comes first for Bioware and Troisi focused on the Bioware way of storytelling.

The “how of interactive narrative”: It is all about choice and how game designers add interactivity into narrative space. That is what makes games as a medium different from movies. In the following, Troisi picked three key design elements that Bioware developed to tell a modern roleplaying game story.

Mass Effect 1 and 2 are “objective” rather than classic “subjective” RPGs

Troisi and his team broke with some holy RPG rules – they replaced the “Subjective”, i.e. the player IS the avatar, through the “Objective”. You are not the avatar anymore, but Sheppard has his own motivation and the player becomes a voyeur watching Sheppard acting on his own. I only remember a Pen&Paper Round where I as a GM started playing somebody`s character, telling how he reacts and that player got really upset. However, Troisi still kept “The Agreement” in order not to completely upset players.

The agreement means, the player should still have the choices he wants and Sheppard`s actions should be predictable with regard to the players’ choice. Troisi showed a scene that didn`t make it in the final version, where the player decided that Sheppard should bargain with a trader and instead, he completely screwed him. Which was funny but not part of the player agreement.

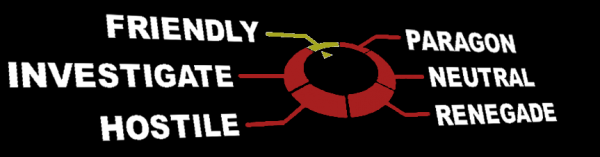

The Bioware “Dialogue Wheel” is an element of interface design to control an “objective” character

An important design element of the GUI is the “Dialogue Wheel” which was so successful that Bioware used it in (the subjective) Dragon Age as well. The player has always the same six choices in the same location so that he intuitively knows which reaction Sheppard will take although the player cannot choose Sheppard`s exact words like in a classic subjective RPG.

Continuing the Mass Effect story across three games: It`s the little differences

An important requirement for ME2 was that it was designed to continue the players` decisions from ME1. 100 pieces of information were taken over, impacting 700 plot hooks (!) in ME2 and many of them were really small and simple. And the best – your story will continue in ME3!

For example, Troisi showed how some ads are changing depending on whether you rescued the Citadel council in ME1 or not. According to Troisi, they put a lot of effort into such small things that maybe 2% of all players will ever see – but these few feel really rewarded. Interestingly, later presenters opposed the Bioware approach and emphasized that they want all players to see everything.

Quick-time events as a way to give the player a choice without interrupting the story

Finally, Troisi justified the so-called “Quick-Time Events” or “interrupts” (reminds me of MtG) they invented for ME2 as an instrument to give the player a choice without disrupting an intense scene. Interestingly, ME2 never gives you both paragon and renegade choices, because “doing nothing” is always an alternative choice as well.

Finally, Troisi justified the so-called “Quick-Time Events” or “interrupts” (reminds me of MtG) they invented for ME2 as an instrument to give the player a choice without disrupting an intense scene. Interestingly, ME2 never gives you both paragon and renegade choices, because “doing nothing” is always an alternative choice as well.

User tests had shown that players were already overstrained with three choices under this time pressure. Like the verbal paraphrase, the quicktime scenes include visual paraphrases, e.g. Sheppard loosening his knuckles in combination with a renegade option means he will get very physical soon…

See part 2 of my Game Design Expo post for a look into the spatial architecture (not information architecture) of Dead Rising 2. Where Fosters and Co. could learn from the Undead…

Related links