A few weeks ago I was at the Storyworlds across Media conference at the Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany. This academic conference revolved around the creation of fictional universes and settings (storyworlds) through a variety of media. This conference was my first real contact with academic narratology and it was most definitely inspiring and interesting.

Over the course of three days I got to meet a set of interesting and intelligent people and talk about a intruiging topics. Of course there also were a number of papers being presented, some of which were quite intriguing while others were rather dry. Videos of all talks are supposed to be made available at the website, free of charge, later on. I’ll briefly try to highlight the, in my opinion, most valuable sessions so that you can give them a look once the videos are online.

Storyworlds across Media

from Marie-Laure Ryan

This introductory talk providfed a good overview over the idea of “storyworlds” and how they fit into theories of narratology. This lecture was a great start to the conference for someone new to the academic discourse on this topic. One of the things I specifically scribbled into my notes was her list of “constituents of storyworlds”, e.g. the things that together can create a storyworld:

- An inventory of existents

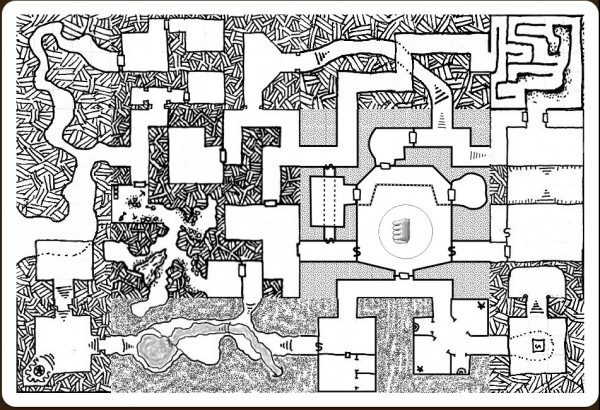

- A space with certain geographic features

- Physical laws

- Social laws and values

- Events. A history of changes that happen in the narrative

- Mental events

What I found especially interesting is that she specifically points out the fictional geography of storyworlds and it’s importance.

A Game of Thrones: Transmedial Worlds, Fandom, and Social Gaming

from Lisbeth Klastrup and Susana Tosca

These two discussed a few transmedial events surrounding the launch of the Game of Thrones TV series, specifically the online games. They made a few interesting observations when it came to the different target groups, how they overlap and interact. Using some low-fi data mining they tried to figure out how readers, GOT enthusiasts, gamers and other people interlocked.

These two discussed a few transmedial events surrounding the launch of the Game of Thrones TV series, specifically the online games. They made a few interesting observations when it came to the different target groups, how they overlap and interact. Using some low-fi data mining they tried to figure out how readers, GOT enthusiasts, gamers and other people interlocked.

The Developing Storyworld of H. P. Lovecraft

from Van Leavenworth

A lecture dealing especially with the slightly odd nature of the Cthulhu mythos and it’s reincarnation in different “texts”. There are a few peciularities since the IP is no longer copyrighted and there is a wide range of different authors. It seems that it’s more of a brand that implies that the text provides a certain sense of world, unifying themes and returning elements. The latter could be locations (Arkham…) or characters (old ones…) but don’t have to be.

Strategies of Storytelling on Transmedia Television

from Jason Mittell

This lecture delved into different methods of sharing the storyworld of a series outside of the TV show. Jason explained two fundamentally different approaches using the examples of Lost and Breaking Bad. The former is expansionist, where the transmedial material expands on the world an adds new histories, characters and events. The Breaking Bad material on the other hand aims to “fold in on itself” to provide denser information about the character themselves, to help viewers get into their heads.

Jason also noted that there are three different kinds of tie-in games to movies and TV shows:

- Exploratory: These games allow you to explore the fictional storyworld yourself.

- Imitational: Games that allow you to “try on the skin” of the story characters. These often fail because the expected drama from TV and Movies is missing.

- Narratively: Games that try to retell the story of the movie in the game. This is almost never done for TV shows. Here the approach is usually to have the game be “one extraordinary episode”.

The Paradox of Interactive Tragedy: Can a Video Game have an Unhappy Ending?

from Jesper Juul

Here Jesper took a closer look at the elements that make up a tragedy and why it’s so difficult to recreate that in games. His theory is that this lies within the paradox of failure. Usually, when we as players succeed in some task within the game, we are happy, as is the protagonist. Likewise, when we fail we are frustrated and suffer, as does our protagonist. In Tragedy however we need to delight at the failure and misfortune of the protagonist. Our long-term aesthetic desire for a well-rounded story has to overcome our short-term desire for the protagonist to succeed, something that’s quite strong in video games.